An ideation/working prototype of a mobile application for use on a smartphone using the Uizard AI-powered user interface. The working title was ‘Whorlsapp’-a guide to identify a textile technology. The intention was to create better accessibility to understanding these whorls when discovered in fieldwork, in post-excavation analysis and for research purposes, Uziard (2018) is an AI design tool, which allows an open access style of design to websites and mobile application. It was proposed that the mobile application would offer a pictorial typology and an overview of the technical functions of what makes a whorl a whorl.

Scraps of Cloths

Archaeological cloth is visible as scraps of a visual chronicle made by women.

Words, women and woad-trickle down effect.

So, a queen in early Ireland had a garden of woad-in Irish-glaisin/glasen.

http://www.dil.ie/search?q=glasen

Is this an example of the trickle-down effect? The effect occurs where the adoption and use of goods and services flows from the top down, the higher social class influences the lower social class. The fact of the queen having a woad garden would set a fashion and woad had a reputation as a universal blue dye as evidenced by archaeological examples:

- Seeds at Deer Park Farm, Co Antrim, 7th century

- Hiberno-Norse Dublin, 9th-10th century

- Seeds in a pot and a dress dyed with woad at Oseberg, Norway, 9th century

- Several Finnish burials of the 8th-11th century had clothing dyed with woad

- An Iron Age burial of a girl wearing clothing with blue and red patterned edges in Denmark

- Bronze/Iron Age, Hallstatt salt mines and its textiles produced evidence of blue dye.

Let us take a closer look at this woad plant in the queen’s garden. Woad is a biennial plant (two-year growth period) and in its first year, it appears as long waxy leaves in a circular arrangement which continues to grow upwards. As we mentioned earlier, it is a member of the cabbage family and therefore, sheep and goats will eat it as the sheep did in the old tale of Cormac’s fair judgement. The second year of growth is when the yellow flowers appear, and the leaves contain very little colour at that stage as its energy is spent on producing new seeds. If we apply this knowledge to the Cormac tale, we can make an assessment that each of the two stages of woad growth were important, year one for dyeing and year two for seeds. However, woad is a plant that is a copious seed producer and when established as a population bank, it is extremely difficult to control and if noting that the woad was termed as the queen’s woad would suggest it was an established woad garden.

This fair judgement from Cormac was to forfeit the fleece of the sheep in compensation for the plants as both will grow again. It was given at the court of Lugaid MacCon and is preserved in a passage from the story of the Battle of Mag Mucrama (Book of Leinster c.12th century). MacCon was considered a corrupt or false king and his judgement was asymmetrical as he wanted the whole of the sheep forfeited and Cormac’s fair judgement exposed him.

If we highlight a section of the fair judgement ‘both will grow again’ we know sheep produce a fleece each year, the woad leaves are produced every second year. Although, if a year one, crop is plentiful, there are several dye methods which vary from a fermentation vat, powder, and dye cakes (remember, the judgement from the legal text Cáin Lánamana: An Old Irish Tract on Marriage and Divorce Law, a woman is entitled to “a third of woad in steeping vats, half if its cake”) hence, it would appear, no year went without access to the blue of the woad plant!

Our research question asked -‘Was there any particular significance in woad dyeing for early medieval Irish women?’ It appears if we consider Cormac, the sheep, the woad plants, and the archaeology then, woad had established its importance prior to the early medieval.

I have harvested the woad leaves and undertaken the procedures to prepare a woad vat, but I am taking a pause here and will not be updating till September 1st.

Words,woad and women-tending the ‘queen’s woad garden’.

Here is a checklist of what we did from October 2019 till August 2020.

- We live in a rural setting and are lucky to have the space to compost. So, after selecting the woad space (9.7 x2.43 m), we agitated the soil and added our own compost from garden and organic household waste. We did not record the weight of the compost.

- In November 2019, we covered the entire area with the two old sheep fleeces (the fleeces weighted approx.4.2kg) and I would recommend using three or four fleeces to cover, more efficient, a space of surface measurement 5.48 m. Unfortunately, we had no access to more fleeces at this time.

- Over the Christmas, we gather seaweed as a fertilizer https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10811-020-02067-7

- We used brown algae commonly called kelp and we took what was on the seashore only.

- We covered the area with the kelp and did not look at the ‘garden’ again till April.

- In early April, we added several layers of compost to the kelp and dug it together, allowed it to settle, raked it over and planted the woad seeds at the end of the month.

- We started off by weeding, regularly, however, woad(Isatis tinctoria) is a member of the family, Cruciferae (cabbage, broccoli, etc) so, it could be a target for slugs, and caterpillars. Therefore, we decided to allow a controlled weed policy to evolve in the garden which resulted in the usual weedy suspects of ragweed and lambs quarter. Our woad seeds (50 planted) had a disappointing yield with only three plants showing. We had hoped for, at least, ten to twenty plants but our seeds were not fresh as I had left the fresh seeds in my office in Dublin!

- The three hardy plants did survive the slugs etc and measured in height 46 cm when we began the harvest on the 6th August of this year.

If we consider how our individual and collective agencies manifested in our woad checklist, we can tick off gendered labour, different age groups working together, a common shared goal and learning opportunities for all concerned. I asked several questions of Michael and Milo regarding gendered labour and the woad garden. The responses varied from familial obligation to interest in what would grow and Milo said woad must be important if the queen in the old story of Cormac had a garden of it!

Words, Woad, and Women-planting in trust and measuring time.

I asked a question, in the last post, “what of the agency of the couple?” as represented by the early medieval law in the text Cáin Lánamana: An Old Irish Tract on Marriage and Divorce Law. This agency occurs from a position of trust, one of the couple, will act for the other with the consent and with the control of the other and, in the case of divorce, the law honours the agency through division. The agency theory, in archaeology, recognises that all persons acted with purpose/s in their environments, each person had intentions with layers of meaning, often, underpinned with several motives. Early medieval law offers to us the lawful representation of agency but how did this law, really, effect how the couple divided the woad in reality? Therefore, I am going to incorporate agency theory to interconnect with the sensory experience with reference to the historical tales of woad and archaeological evidence with testing and repeating through experimental archaeology. I am not adding rather I am offering support to the project through agency theory.

The project work started in October 2019 with the clearing of a space in my own garden in Co. Wexford, Ireland (measurements etc included in next post). There was, no point in preparing a ‘queens woad garden’ in the Centre for Experimental Archaeology and Material Culture, UCD, Dublin were my office is located. The reason influencing this decision, was distance as I wanted to prepare and tend the soil in a different fashion using sheep fleece and seaweed. The use of fleeces is not new, there is good evidence that sheep’s wool holds moisture, it warms plant roots during winter and acts as a weed barrier. The use of seaweed is a recognised organic fertilizer which can provide extremely rich nutrients to the soil. My home soil is coarse rather sticky clay with a poor draining quality so, picking the location within the garden was important-an excellent resource was: https://www.teagasc.ie/crops/soil–soil-fertility/county-soil-maps/.

In selecting the location, I used a ‘working example’ of agency theory, individuals working as a collective in a created ecosystem (I apologise for my very simple explanation and lack of references but this is a blog posting after all). The present-day individuals operating in the format of who did what and where, were me, Dolores Kearney, my husband Michael, and my grandson, Milo. Each of us have different individual and collective agency, my husband and I would (re)construct the ‘couple agency’ and my grandson is atypical in his thought patterns so his agency would add a neurological angle.

I explained the five basic scientific steps to Michael and Milo, in relation,to what was expected in the project, words, woad, and women.

- Starting with an observation on thinking about connections between early medieval women and woad dyeing processes.

- From there, the research question-‘Was there any particular significance in woad dyeing for early medieval Irish women?’

- The hypothesis-the historical sources have recorded the use of woad, the archaeological record has recorded evidence of its use in the early medieval period, and if we add on a (re)construction of the practices of woad planting, harvesting and extraction, can we ascertain if there was any specific importance in woad dyeing for early medieval women.

- The chemical experiment of woad dyeing itself-planting from seed, harvesting and pigment extraction and dyeing of wool and linen.

- Conclusions

We are using experimental archaeology in its exploratory contribution, not its controlled contribution for this blog, just to be clear as,again, blogs are handy sounding places.

On a personal level, I, quickly, realised that Milo had no concept of a distant past. Therefore, explaining a periodisation was challenging but we talked about ‘this time and old time’ as we gathered the seaweed and prepared the old fleeces for use in the small plot below.

Words, woad and women:wise actions and the price of divorce.

In my first post on Wednesday, I mentioned law tracts and the tales of kings and heroes. This literature of early medieval Ireland interconnected to give legitimacy to rule in early Ireland. One kingly tale connected to woad is known as the fair or just judgement of Cormac MacAirt. This man, Cormac is on his way to Tara (seat of Irish kingship) when he meets a steward and a woman whose sheep have eaten the queen’s woad. As a fine/penalty price, the sheep are to be killed or confiscated from the woman. However, in his wisdom, Cormac, not yet king, says the fleeces of the sheep should be given as payment for the consumed woad plants as both fleece and plants will grow again.

For those interested in these early Irish cycles (modern classification) tales, the cycles are divided into four; the Ulster cycle (the hero tales); the cycle of Kings (where historical and hero overlap); the Mythological and the Finn cycle (where myths and hero legends intersect). The link here is for one of the famous tales, The Táin, from the Ulster cycle: https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T301035.html. J.P. Mallory in his book-In search of the Irish Dreamtime notes how the early Irish cycle tales coloured-coded the clothing of their kings and heroes thus appealing to and promoting the sense of the visual to the listener and, in later years, to the reader (Mallory 2016, 229-30).

The early medieval Irish law tracts that have survived are laws like all laws that have value, to inform, to organise, and to exercise control. A woad example comes from the legal text Cáin Lánamana: An Old Irish Tract on Marriage and Divorce Law. Concerning woad plant, it states: a woman is entitled to “a third of woad in steeping vats, half if its cake”. The value to inform, organise and control are all present in this law but, pause and think, what of the agency of the couple? Bearing this question on agency in mind and with a handful of woad seeds, we, not I, set out to grow the woad, harvest it, and extract the blue pigment.

Words, Woad, and Women: mothers with saints for sons.

Words, Woad, and Women: mothers with saints for sons.

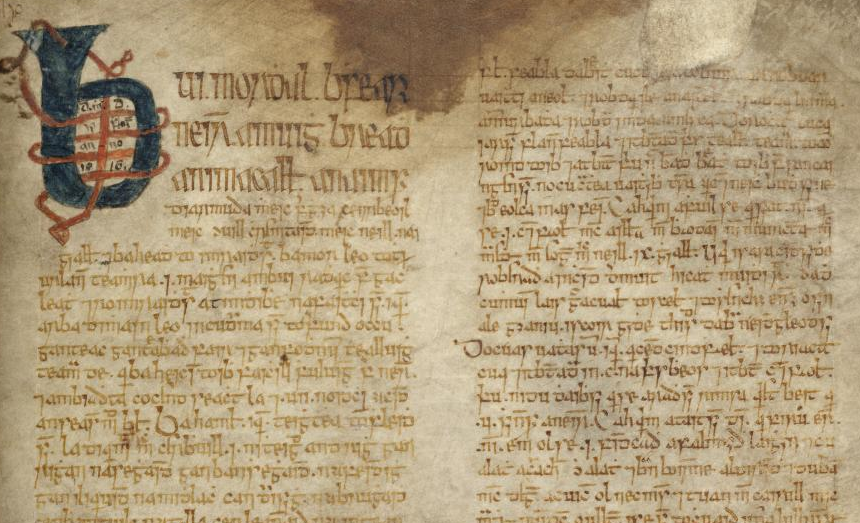

This morning (August 13th), I want to share a delightful, dye tale of mother and son from the Irish Life of St Ciarán. St Ciarán (c. 6th century) was a gifted student and zealous monk, the abbot and founder of Clonmacnoise Co Offaly, Ireland. Their dye tale was recorded in a manuscript called the Book of Lismore. This is a patron book from the late, 15th century, it is a transcript from an earlier textual source. When we read, any, saints’ lives, we must be aware that, the lives follow a prescriptive literary structure and are, often, chronologically suspect hence, the responsibility of any researcher is to assess how this type of literature functioned in its prime.

This life of St Ciarán was written in middle Irish, in contrast, to his other lives which were written in Latin. This life is the only life with a homily introduction, indicating, it had a public function and reception. Hillary Powell (2010) developed an assessment of the role of folklore in Anglo-Latin saints’ lives. Her results indicated the lives functioned as a style of script for performances on saint’s feast days. This ‘script’ of the Irish Life of St Ciarán was the only, one of his lives to contain this dye tale. A story that is layered with revelatory glimpses of gendered labour and pagan leanings with Christian admonishments for those leanings, it features chemistry at work and the perils of interrupted experiments.

The tale is in a domestic setting and it involved St Ciarán, his mother and a vat of plant dye called woad. Woad (Isatis tinctorial) is a dye plant that produces a blue dye.

In 1994, Maire Herbert published a translation of this tale:

“ On a certain day, Ciarán’s mother was making blue dye and she was on the point of putting clothing into it whereupon his mother said to him: “Out with you Ciarán! It is not considered auspicious to have men present for the process of dyeing cloth”

“May there be a grey stripe on it so” said Ciarán. Of the amount of cloth that was put into the dye there was none without a grey stripe.

The dye was made again, and his mother said to him: “Go out now, Ciarán, and let there be no grey strip in it this time”. Then he said:

“Alleluia, Lord. May my mother’s blue dye be white. Every time it comes to me, may it be as bright as bone. Every time it comes to be boiled may it be as white as curd”. Indeed, every cloth which was put into it was completely white afterwards.

The dye was made a third time. “Ciarán” said his mother “ do not ruin the dye for me this time but rather let it be blessed by you”.

Ciarán had blessed it, there was no dye made previously or subsequently which was as good as it”.

The reading aloud of this tale is used to attract, to relate and hold the attentions of many different audience members, it has kinetic imagery. Remember, all the saints lives and, this one is no different, have agendas attached but exploring those agendas are ecumenical matters! Our interest is in, how the dye tale functions within itself. Natural dyeing is chemistry and results will vary occurring to the number of variables across the processes which are used to achieve the desired outcome, but the most important aspect is the repeatability. All the misfortunes of the woad dyeing processes in the tale can be explained by miscalculations. I have attached here a link to an excellent article-‘Searching for blue: Experiments with woad fermentation vats and an explanation of the colours through dye analysis’ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352409X14000273. And, over the next few days, I will recount my ‘delightful tale’ of woad dyeing.

Words, Woad, and Women.

As you may be aware, I am working through my PhD on Irish textile production using archaeology, historical evidence, and experimental archaeology to explore the materiality of women’s lives in early medieval Ireland, AD 500-1100. One aspect of textile production is the dyeing of wool or cloth and I wanted to gain, through dyeing practices, an insight into early Irish women’s lives. However, that is a too broad a statement to make, an insight of mine is not measurable. Therefore, the need arises to use a specific structural framework consisting of historical sources, the archaeological record, the scientific method of experimental archaeology, and the consideration of sensory perception. The aim is to create a four-part, investigative process with interpretative results.

Fortunately, Ireland has a wide-ranging, extant body of early medieval literature from the heroic biographies and king tales to saint’s lives alongside a corpus of law tracts. Dye plants and colour feature strongly in this literature, particularly, the blue dye extracted from the woad plant (Isatis tinctoria). Woad seeds were excavated from several early medieval settlement sites alongside madder seeds (another documented plant dye) indicating an established, at least, household production model for dyeing processes. If we add in experimental archaeology, we have deductive analysis with the scientific method.

Firstly, let us examine, what can we gain from the use of experimental archaeology through the scientific method.

Starting with an observation:

‘I want to explore an aspect of early medieval Irish women’s materiality and I want to do so through the practical processes of dyeing highlighting woad as a specific example’.

To expand out this observation, historical and archaeological evidence is required. It appears woad and its resultant blue colour featured across a genre of early medieval Ireland literature and the archaeological record gives credence to this written evidence however, if I want to use the process of woad dyeing to gain insights into early medieval women’s materiality (the contextual and connecting experiences of material life), I need to ask a question:

‘How important was dyeing cloth in the lives of early medieval Irish women?’

Again, the question is quite wide in its asking, therefore, lets narrow it down:

‘Was there any particular significance in woad dyeing for early medieval Irish women?’

Reading the literary sources have prompted the last question and the use of the word ‘any’ will allow for the inclusion of cultural, economy, social or religious significance hence, the ability is there to amplify the question. The next step on from the question is the formation of a testable explanation, I can grow woad, I can process woad, all testable (re)constructed actions but can these actions explain the question? No, because the actions, techniques, and practices, like these, are embodied knowledge. Although, if I combine the literature with the archaeological record, follow the scientific method and consider applying a sensory experience model to interpret an active position of people and their ‘stuff’ as rooted into their cultural, and economic settings, I predict, it is possible to provide a measurable interpretational strategy for the research question with repeatability.

I will post updates daily between now and the 21st August 2020.

Archaeologia VII-1785. Part I.

Elizabeth Rawdon, Countess of Moira was the author of the following, what we today would call a journal article. However, in the 18th century, archaeology was only in the making and the involvement of women, even women with wealth and titles such as the countess, was conducted through male intermediators as we can see from the full title:

‘Particulars relative to a human skeleton and the garments that were found, thereon, when dug out of a bog at the foot of Drurnkeragh, a mountain in the county of Down and Barony of Kinalearty, on Lord Moria’s estate, in the autumn of 1781’ in a letter to the Hon. John Theophilus Rawdon (her son) and communicated by Mr Daines Barrington, (member of the Society of Antiquaries)

From her Dublin home at Ussher’s Island, the countess ran an intellectual salon for over forty years. This culture of the salon emerged from the Age of Enlightenment and provided a structure where women had a leading role, deciding the topics for analysis and discussion. The countess’ salon was a leading light in the literary, and antiquarian circles in Dublin. Her archaeological investigation of the bog body discovered on her husband’s county seat was systematic and methodical given the evidence that was available.

The body was described as a small woman buried with many garments. She was, originally, discovered at 11 ft beneath the bog but when the countess asked for the garments so she could gain evidence of medieval wool and linen production in the province of Ulster. She received only fragmentary samples and over the course of the next blog posts, I intend to examine what the countess was given, how she analysed the evidence and discussed it.

Seeking Crafters!!!

Call out to combine theory with practice over the summer months.

I am seeking expressions of interest from textile crafters willing to discuss and practice textile skills. I am hoping to contact textile crafters living along the east coast of Ireland but will consider online tutorial/discussion styles too.

Currently, I am studying for my PhD in early medieval Irish textiles and a key aspect of this project is the utilisation of experimental archaeology. The aim is to understand the transfer of knowledge through action practice and translating that action into a disseminating format.

If interested, please comment or message me at Early Medieval Textiles Ireland and beyond-Experimental Archaeology Facebook page. Thank you in advance.